‘Sittin’ in the kitchen, a house in Macon

Loretta’s singing on the radio

Smell of coffee, eggs and bacon

Car wheels on a gravel road’

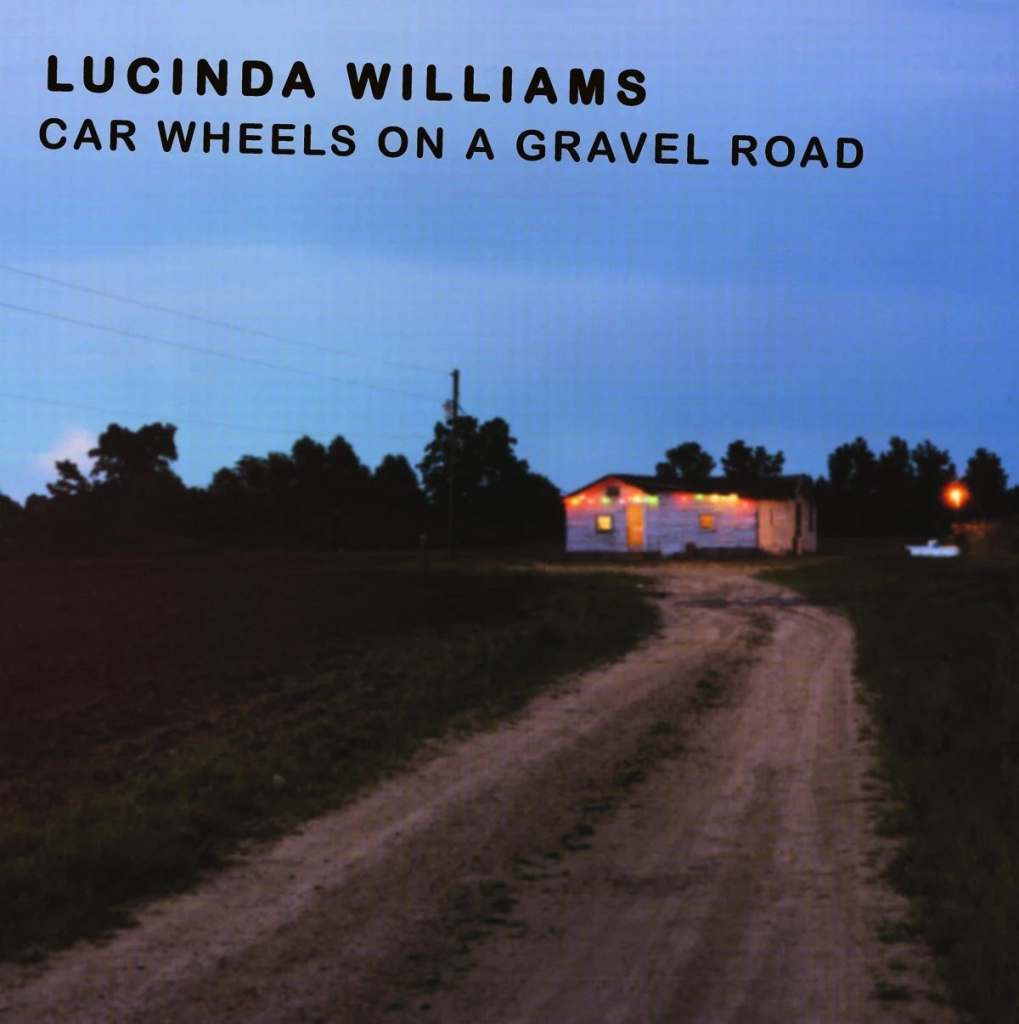

Quarter of a century ago, at the mid point of 1998, Lucinda Williams released her fifth and best-selling album Car Wheels On A Gravel Road. It was an album that undeniably helped to define a burgeoning new genre/label that would come to be called Americana. The record went on to win a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 1999 and cement Williams’ place as one of the finest songwriters of her generation.

The path to release wasn’t a smooth one though, that gravel road had many roadblocks, speed humps and dangerous curves beginning with a protracted recording process. Initially under the helm of producer and guitarist Gurf Morlix in Austin, Texas in 1995, the sessions shifted to Nashville Tennessee later in the year, where problems began to arise. After being part of a session for a Steve Earle album, with Earle and Ray Kennedy producing, Williams became dissatisfied with the sound of her new recordings and hired Earle and Kennedy to re-record some of her album. Three cooks in the studio kitchen led to production conflict with Morlix and his subsequent resignation from the role.

Eventually the album was completed, after yet another delay due to American Recordings changing their major label distribution in 1997 and Mercury Records subsequently buying the masters of the finished album. Three years had passed since the songs of Car Wheels On A Gravel Road began their journey into the wider world but finally in June of 1998 the album was released.

If you listen to the album back-to-back with the preceding Sweet Old World, you’ll be struck by how much she shifted sonic gears from the raw and thin country-folk sound of that album, taking her songs into a decidedly more 90s roots-rock sound. The realisation of how her songs could sound, if recorded differently, no doubt played a big part in her beautifully re-recording Sweet Old World in its entirety in 2017.

A warmer, more ‘produced’ sound also meant the album would appeal to a wider range of listeners, greatly increasing her fanbase in the process. It was the sound of an artist taking a big step forward, Williams’ voice taking centre-stage and giving added weight to her tales of heartache and the Deep South. In addition, the album was graced by a who’s who of alt-country artists, all still strongly in the game. Steve Earle, Buddy Miller, Jim Lauderdale, Emmylou Harris, Charlie Sexton, Greg Leisz, Roy Bittan (The E Street Band) and others all contributed key parts to the effortless ache and melancholic country sway and twang of the music.

Williams set her songs in the Deep South, name-checking places such as Macon, West Memphis, Lake Charles, Louisiana, Baton Rouge and Rosedale, Mississippi. By placing characters within these locations she successfully combined the macro and the micro – emotive dots on the landscape connected by the universality of their experiences. On the album’s closing song ‘Jackson’ she’s putting literal and figurative distance between the narrator and the song’s ex-lover.

From the geographical settings of the songs to a landscape of fractured relationships, regret and guilt, she perfectly dissects the rough terrain – from hearts in bloom to heartbreak and its aftermath.

“Not a day goes by I don’t think about you, you left your mark on me, it’s permanent, a tattoo. Pierce the skin and the blood runs through,” she sings on the opener ‘Right On Time’. By track 11 she’s singing “I know it’s over ‘cause you told me so. I tried to leave but I can’t let you go. I can’t believe you don’t want me no more. Still I long for your kiss.” On ‘Joy’ she’s desperately and defiantly trying to find joy once more, maybe in West Memphis.

Reality and fiction intertwine across the album, with ‘Drunken Angel’, an towering highlight written about murdered songwriter and friend Blaze Foley. On ’Lake Charles’ Williams’ remembers ex-boyfriend Clyde Woodward who also died prematurely, long after the pair split up.

Though there’s a slick, high-res quality to the recordings, like Petty in his commercial prime, there’s also a strong connection back to the dirt and dust of the countryside, particularly on songs such as ‘Concrete and Barbed Wire’. Like a back porch session, it’s Williams at her most relaxed and countrified, a timely reminder of the roots of her music and that Southern drawl.

Car Wheels On A Gravel Road would be the opening chapter of the next part of Williams’ career. A major signpost of her poetic creativity – sometimes tender, sometimes caustic – that she’d explore across the next 25 years, along the way influencing a whole generation of Americana songwriters.

CHRIS FAMILTON